What is the Ecological Model of Health?: Using Circulatory Disease to Explain the Model

According to a report done by my workplace, the Haliburton, Kawartha, Pine Ridge District Health Unit (2012), the leading cause of death for residents of this region from 2000-2011 was identified as diseases of the circulatory system. With this in mind, I am going to examine the ecological model of health using circulatory system diseases as an example to help demonstrate how the model can be applied to a health issue.

To begin, it is important to understand what the ecological model of health is. According to Dustin, Bricker and Schwab (2010) the ecological model of health defines health as a symbiotic relationship between the individual, their community and the environment, and they note that "the individual cannot be healthy independent of the condition of the larger community, and the larger community cannot be healthy independent of the condition of the individuals constituting it" (p. 7).

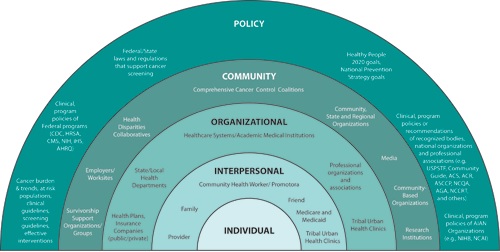

The ecological model of health is composed of several levels in a tiered system, including the individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and social/policy (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013; Women's and Children's..., 2013). In this model, the individual is the base of the system with the proceeding levels acting as influencing factors on the individual's overall health (CDC, 2013).

Level 1: Individual

Level 1 of the ecological model of health is the individual. Within this level, factors affecting one's health can include genetics and personal behaviours (Women's and Children's..., 2013). Genetics can be an obvious risk factor for circulatory disease as, for example, if you have a familial history of stroke or heart attack, then you may be at increased risk for developing these same issues (CDC, 2013). Additionally, personal health behaviours, which is identified as a SDOH (MOHLTC, 2018), can impact your risk of developing circulatory disease, as choosing behaviours like smoking or living a sedentary lifestyle are risk factors for developing circulatory disease (CDC, 2013; Government of Canada, 2009).

Furthermore, thinking back to Dustin, Bricker and Schwab's (2010) definition of the ecological model of health, where the health of an individual is symbiotic with their environment, we can see that unhealthy behaviours such as smoking that result in poor health for the individual can also result in poorer environmental conditions, as second hand smoke is a pollutant and therefore creates an unhealthy environment. This demonstrates the symbiotic relationship between the individual and the environment.

Level 2: Interpersonal

Level 2 of the ecological model of health is interpersonal factors. Factors within this level can include family, culture, traditions, and friends (Women's and Children's..., 2009). Thinking about family customs and traditions, people who grow up in a culture or a family where the traditional food dishes tend to be high in fat and contain low amounts of vegetables are at risk for developing circulatory diseases (Government of Canada, 2017). The Government of Canada notes that Canadians with African, Chinese, Hispanic or South Asian origin tend to have a high rate of heart disease related to their cultural diet and activity norms (Government of Canada, 2017). Relating this back to the SDOH, culture, race, ethnicity, and food insecurity are all identified as SDOH in Ontario and Canada (MOHLTC, 2018).

As another example within this level of the ecological model of health, we can look again at the SDOH and see that socioeconomic status is one of the determinants that fit within this level. For example, if we come from a family with a lower socioeconomic status, statistics show that we are more likely to be subject to food insecurity which results in consuming an unhealthy diet due to lack of resources to afford healthier foods, which ultimately increases our risk for developing poor health conditions such as circulatory disease (Government of Canada, 2017).

Level 3: Institutional

Level 3 of the ecological model of health is institutional factors which can include things like our work and school environments (Women's and Children's..., 2013). Using myself as an example, my workplace has a committee responsible for workplace nutrition. From this committee, staff members receive emails promoting healthy eating habits, most notably during national nutrition month which takes place each year in March, and this committee has removed all vending machines from our offices to try and eliminate easy access to non-nutritional snacks. As an alternative to vending machines, the committee frequently places apples and other sorts of healthy snacks in our lunch rooms for staff to snack on. Looking at this example, we can see how institutional factors can impact our risk of developing heart disease, as in my example it is noted that all vending machines have been removed which promotes healthier snacking but if I were in a workplace or a school where vending machines were easily accessible and often relatively cheap, I would likely snack on sugary and fatty foods which can increase risk for developing heart disease (Government of Canada, 2017).

Level 4: Community

Level 4 of the ecological model of health is the community (Women's and Children's..., 2013). Community factors that can influence an individual's health can include things like access and affordability, community structures, the media, and community supports (CDC, 2013; Women's and Children's..., 2013). Looking specifically at community structures and access and affordability, I reflect on the community where I work and how this looks. My workplace is located in a residential area and is directly across the road from a fast food restaurant. There are several other fast food restaurants within an approximate 400 meter radius from my office, and there is a grocery store located approximately 3 kilometers away. There are no gyms in the town where I work, however, there are several gyms located in the neighbouring town. Now thinking about the SDOH, specifically physical environments (Government of Canada, 2018; MOHLTC, 2018), it is easy to see how the community I work in is not conducive to preventing circulatory diseases. We can see from my description that healthy food options are not the most accessible and the promotion of physical activity is not strongly built into the community environment, which are both risk factors for developing circulatory disease (Government of Canada, 2017).

Level 5: Social/Policy

Looking at the fifth and final level of the ecological model of health, that being the social/policy level (Women's and Children's..., 2013), factors within this level that can affect health include organizational and government policies (Women's and Children's..., 2013). One specific example that comes to mind when thinking about this level is Canada's Food Guide (Government of Canada, 2011). Canada's Food Guide (2011) specifically states that following the recommendations in the food guide can reduce your risk of obesity and heart disease. By having a formal and recognized standard for healthy eating in Canada, this can help promote proper dietary choices and can act as a tool to guide people to eat healthier and therefore decrease their risk for circulatory disease. Unfortunately, thinking back to the SDOH, food insecurity, income, and physical environments can be barriers to following the food guide and can result in poor eating and ultimately increased risk for heart disease (Government of Canada, 2017; Government of Canada, 2018).

Another example that can help to demonstrate this level of the ecological model of health is the Smoke-Free Ontario Act, 2017. This act outlines many rules and regulations for smoking, but one specific point within this act that I would like to highlight is that adults may not smoke in a vehicle when any person 15 years of age or younger is inside it (Government of Ontario, 2017). Since smoking and exposure to second-hand smoke are identified as major risk factors for circulatory disease (Government of Canada, 2017), we can see how this is an excellent public policy in Ontario to help decrease the impact smoking has on people in Ontario for developing circulatory disease, and more specifically, we can see how it helps to protect the health of children and youth who are often negatively impacted by the environments they are raised in as childhood experiences is an identified SDOH (Government of Canada, 2018).

Conclusion

The ecological model of health can be used in health care as a tool to guide health promotion initiatives (Women's and Children's..., 2013). The ecological model of health suggests that the social and physical environments we live in "shape the patterns of disease and injury as well as our responses to them over the entire life cycle"(as cited in Women's and Children's..., 2013), so by knowing this, we should look at our communities and identify what the patterns of disease are that we are seeing, how individuals and communities are responding to these diseases, and what we can do to change the responses and behaviours in order to achieve healthier outcomes.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013). National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP): Social Ecological Model. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/nbccedp/sem.htm

Dustin, D., Bricker, K. & Schwab, K. (2010). People and nature: Toward an ecological model of health promotion. Leisure Sciences, 32, 3-14. DOI: 10.1080/01490400903430772

Government of Canada. (2011). Canada's Food Guide. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/fn-an/alt_formats/hpfb-dgpsa/pdf/food-guide-aliment/view_eatwell_vue_bienmang-eng.pdf

Government of Canada. (2017). Prevention of heart diseases and conditions. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/heart-health/heart-diseases-conditions/prevention-heart-diseases-conditions.html

Government of Ontario. (2017). Smoke-Free Ontario Act, 2017, S.O. 2017, c. 26, Sched. 3. Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/17s26#BK22

Government of Canada. (2018). Social determinants of health and health inequalities. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health.html

Haliburton, Kawartha, Pine Ridge District Health Unit (HKPRDHU). (2012). Leading causes of death in the HKPR district, 200-2011. Retrieved from https://www.hkpr.on.ca/Portals/0/PDF%20Files/PDF%20-%20Epi/EPI%20-%20Leading%20Cause%20-%202015-06-04.pdf

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. (2018). Health equity guideline. Retrieved from https://health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/protocols_guidelines/Health_Equity_Guideline_2018_en.pdf

Women's and Children's Health Policy Centre: John Hopkins School of Public Health [Randy Miller]. (2013). An introduction to the ecological model in public health [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xhUxOZRn_4E